Twenty-five years ago this week, India’s government betrayed the people of Rakhine State in western Myanmar, when its armed forces smashed a nascent Rakhine revolutionary group in a remote part of the Andaman Islands.

In the years since, the Indian government has never referred publicly to the incident, but it continues to resonate among the Rakhine people, who remember it as Gen. Khaing Raza’s Day, or Betrayal of India over Rakhine Revolution Day. In a 2009 book, the prominent Indian human rights lawyer Nandita Haksar described the incident as “infamous.”

On the morning of February 11, 1998, the Indian military launched a brutal operation codenamed Leech, in which it raided Landfall Island in the Andaman Sea, arresting at least 73 people, and killing at least six rebels. These included the Arakan Army commander Gen. Khiang Raza and Maj. Soe Tun and two leaders of the Karen National Union.

As the India-based news outlet Quint reported in 2019, 35 of the 73 people arrested were fishermen and were released after a year of detention on the island; two were Thai boatmen who were also released; two more reportedly tried to escape and went missing. The remaining 34 people were Rakhine and Karen rebels from Myanmar. Their trial took place in secret, and they were held in jail for 13 years, six-and-a-half of those years without charge. The 34 men were only released in 2011, when they were granted refugee status by the United Nations refugee agency and resettled in the Netherlands.

The violent incident brought to a premature end the first serious attempt to form a Rakhine nationalist resistance against Myanmar’s military junta. The Arakan Army (AA) was initially formed in February 1991 by a group of patriotic Rakhines including Gen. Khaing Raza, with support from the Karen National Union (KNU), on the Myanmar-Thailand border. Shortly after its formation, at least 60 AA rebels attempted to travel from southeast Myanmar to Rakhine State on the Myanmar-Bangladesh border in early May 1991. The group confronted clashes for a month with the Myanmar military, and only 40 of them arrived at the border safely. In 1992, and 1993, the group sent a couple more consignments of troops and weapons from the Myanmar-Thailand border to the Bangladesh border area.

In January 1994, at least four Rakhine revolutionary groups made the historic decision to merge into a single organization: the National United Party of Arakan (NUPA), with an armed wing, also known as the Arakan Army (AA). The group’s goal was home rule for the Rakhine. The AA was at this point re-formed under the leadership of seven commanders, including Gen. Khaing Raza and Maj. Saw Tun. By 1997, the strength of the army had grown to 500 troops armed with some 200 rifles, and it had established a small naval force.

India’s Betrayal

After the Arakan Army (AA)’s formation in 1991, Khaing Raza established a good relationship with officers from the Research and Analysis Wing (RAW), India’s foreign intelligence agency, with whom he regularly shared information. Three years after the Rakhine revolutionary groups merged in 1994, these relations improved further and RAW officers eventually introduced Khaing Raza to a number of Indian military commanders and intelligence officers. Chief among these was the military intelligence officer Lt.-Col. Biswajit Singh Grewal, who notably had been born in Myanmar and studied at the University of Mandalay, and was fluent in the Burmese language. (He even had a Burmese name, Nay Win). In January 1995, Lt.-Gen. Pradeep Chandran Nair, commander in chief of the Assam Rifles, visited the NUPA/AA base along the India-Myanmar border, and met with Khaing Raza.

Former Rakhine marine leaders (from left): Maj. Kyan Sein Maung, Maj. Khine Kyaw Khine, Gen. Khaing Raza, and Capt. Mra Aung. (Photo courtesy of Maj. Khine Kyaw Khine)ADVERTISEMENT

In early 1997, the NUPA/AA and KNU top leaders decided to establish a base in the Andaman Sea, to provide them access to the Ayeyarwady River delta in southern Myanmar. Maj. Saw Tun spoke to Lt. Col. Grewal, who initially allowed the NUPA/AA to set up a base first on Narcondam island, and then on Landfall Island, in the north of the Andaman Islands chain, around 300 kilometers from Myanmar’s coast.

A month later, Saw Tun was taken to Landfall Island on an Indian Army flight, alongside Grewal. In May of that year, the NUPA/AA marine commander, Maj. Khaing Kyaw Khaing, and his group had attempted to reach the island by sea, but they gave up due to a heavy storm in the area. Next month, Grewal flew to Bangkok to meet with KNU and NUPA/AA leaders, and agreed that they could relocate to the island on February 11, 1998.

On February 8, 1998, a group of 40 men – 27 from the NUPA/AA and 13 from the KNU – led by Khaing Raza and Saw Tun departed for Landfall Island in two ships from the coast of Tanintharyi Region in southern Myanmar. They arrived on the evening of February 10 and slept one night there.

Then, early the next morning, Indian military officers, including Grewal, launched Operation Leech, executing at least four leaders from the NUPA/AA including Khaing Raza and Saw Tun, two KNU leaders, and two other Myanmar rebels. As mentioned above, the remaining 34 were taken into custody.

The Indian military informed New Delhi that Operation Leech had smashed a group of “gunrunners” who had been aiding anti-Indian separatists in the country’s northeast. However, former Khaing Kyaw Khaing, formerly one of seven founding commanders of the AA, told this author recently that the leaders aimed to fight the military regime in Myanmar, and went to Landfall Island trusting India’s promise that it would allow them a safe haven there. He said that the Indian military completely destroyed the embryonic Rakhine revolutionary force, describing it as an unforgettable betrayal of “all of our Arakanese.”

Lt. Gen. Pradeep Chandran Nair, commander in chief of the Assam Rifles (center, in blue shirt), during a visit to the NUPA/AA base along the India-Myanmar border, January 23, 1995. (Photo courtesy Maj. Khine Kyaw Khine).

Indeed, DB Nandi, a former Indian intelligence officer and RAW deputy chief who worked in Myanmar, told The Guardian in 2007 that the Indian military operation was explicitly intended to destroy the Rakhine revolutionary movement. In 2019, Grewal, now retired, told local news outlets that the operation was not carried out on the army’s own initiative, and that it had approval from New Delhi.

After the events on Landfall Island in 1998, few people in western Myanmar believed that a Rakhine rebellion against the Myanmar military could succeed, given India’s evident hostility to the cause and the group’s inability to establish a base along the Myanmar-India border. It was only since the rebirth of the Arakan Army in 2009 that these dreams of Rakhine home rule have stirred back to life.

The New Arakan Army and Its Relations with New Delhi

Fifteen years after the Indian army smashed the NUPA/AA on Landfall Island, another version of the Arakan Army was formed by Maj. Gen. Twan Mrat Naing and 25 comrades in April 2009 in Laiza, on the Chinese border in Kachin State, with support from the Kachin Independence Army (KIA).

In the years since, the AA has grown considerably. It now has 30,000 troops under arms, mainly in Rakhine State, though at least 6,000 troops are stationed in areas controlled by the AA’s allies in the north and northeast of the country. Recently, the group’s political wing, the United League of Arakan (ULA), claimed that it enjoyed de facto control over two-thirds of Rakhine. During 2018-2020, analysts described fighting between the AA and the Myanmar military as the fiercest Myanmar had seen in decades.

Relations between the New Delhi government and the ULA/AA during the armed conflict of 2018-2020 have been curious. Although India is the world’s largest democracy, its government has traditionally maintained good relations with Myanmar’s military. From February 17 to March 2, 2019, amid fighting between the AA and Myanmar military in Rakhine State, the Indian military took part in the joint Operation Sunrise with the Myanmar military against the AA in the India-Myanmar border area. Its operation was intended to eliminate the AA from the border region, where India is hoping to implement the Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project connecting Mizoram to Kolkata via Rakhine State’s capital Sittwe.

The Indian government seemingly believed that the armed movement of the ULA/AA was just a temporary uprising and that the Myanmar military would eventually be able to eradicate the insurgents. However, the armed conflict of 2018-2020 ended with AA still in control of its main strongholds in Rakhine, which seems to have shifted opinion within Indian decision-making circles about the need to negotiate with the ULA/AA. On August 11 of last year, for instance, the ULA/AA spokesperson said in an online press conference that the group had taken part in negotiations with New Delhi on the implementation of the Kaladan project.

However, the Indian government still hasn’t openly engaged with the ULA/AA, and in order to maintain good relations with the Myanmar military, has remained mostly silent about the atrocities committed by the military since its coup on February 1, 2021, despite the junta arresting over 17,000 and killing nearly 2,900 of its own citizens, including children. Instead, the Indian government is trying to finalize and implement the Kaladan transport project. On January 9, India’s Union Minister Sarbananda Sonowal said the project was “ready to operate.”

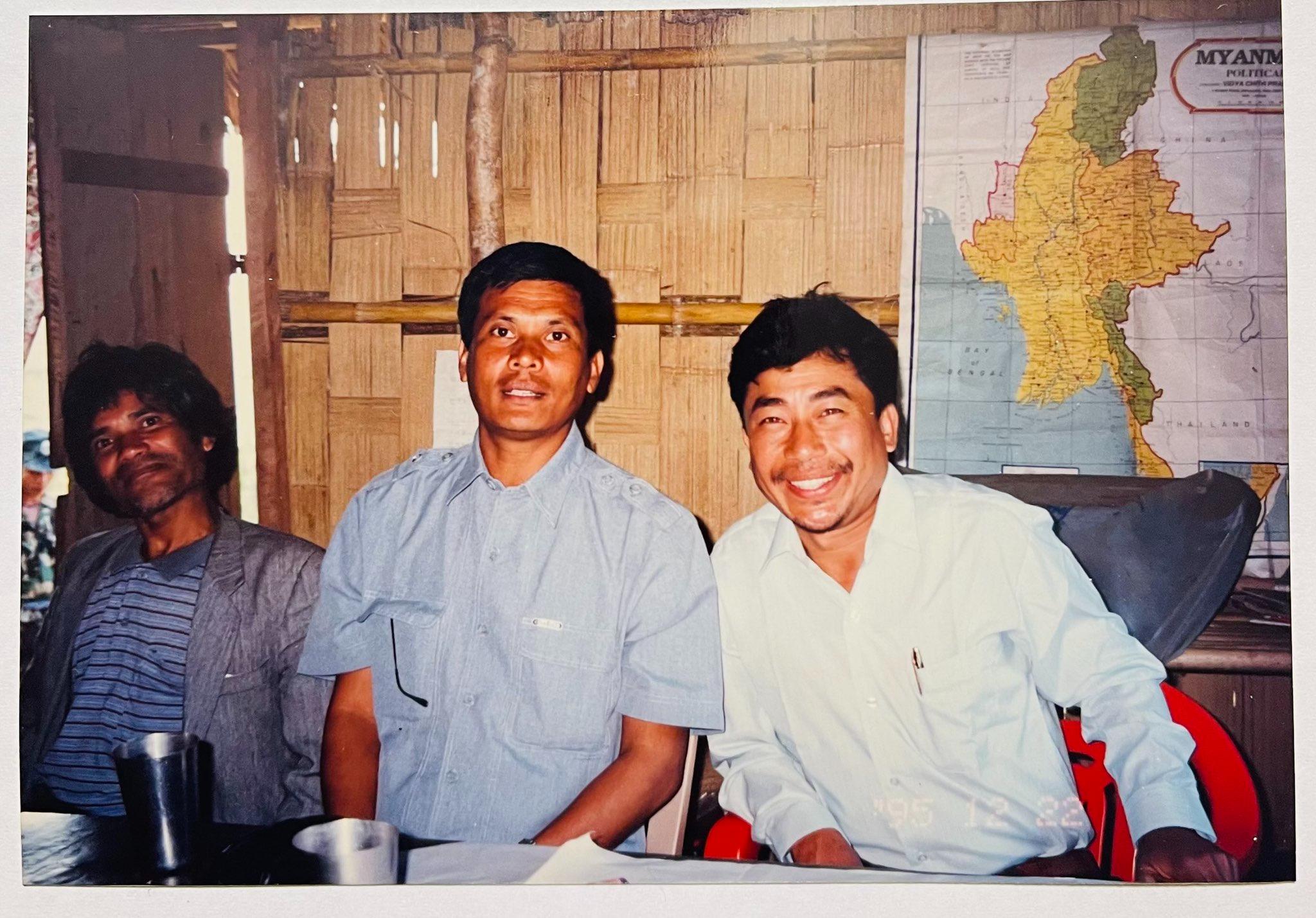

NULA/AA officials Khaing Mra Wa, Gen. Khaing Raza, and Maj. Khine Kyaw Khine after meeting with officers from the Indian intelligence agency RAW, at the Vara Va camp in the India-Bangladesh-Myanmar border area, December, 22, 1995. (Photo courtesy Maj. Khine Kyaw Khine)

Overall, India’s current approach toward Myanmar is puzzling. The local security apparatus in India’s eastern provinces has frequently arrested not just the members of the anti-junta resistance but also refugees who have fled across the Myanmar-India border due to Myanmar military attacks. Another critical issue is the fact that the Myanmar junta forces have used Indian rebel forces to stage attacks against the resistance in the upper Sagaing Region, close to India’s border.

However, the growing strength of the Rakhine movement for home rule, led by the ULA/AA, demonstrates that New Delhi’s strategy toward the current junta is serving neither its national interest nor the interests of the Myanmar people. When it comes to the Kaladan project in northern Rakhine State, a priority for New Delhi, the government’s current approach is mostly counterproductive, given the ULA/AA’s influence over the Rakhine State.

Now is the time for New Delhi to remedy the mistakes in its policy toward the Rakhine conflict and the country’s anti-junta resistance movement more broadly. A good place to start would be to acknowledge India’s betrayal of the Rakhine revolution in 1998 and atone for its past mistakes by forging a new cooperative path with the Rakhine people.

Source : The Diplomat